Digital Assistants or Digital Dependents?

"Hey Google, what's the weather like today?" "Alexa, add milk to the shopping list." "Siri, navigate home."

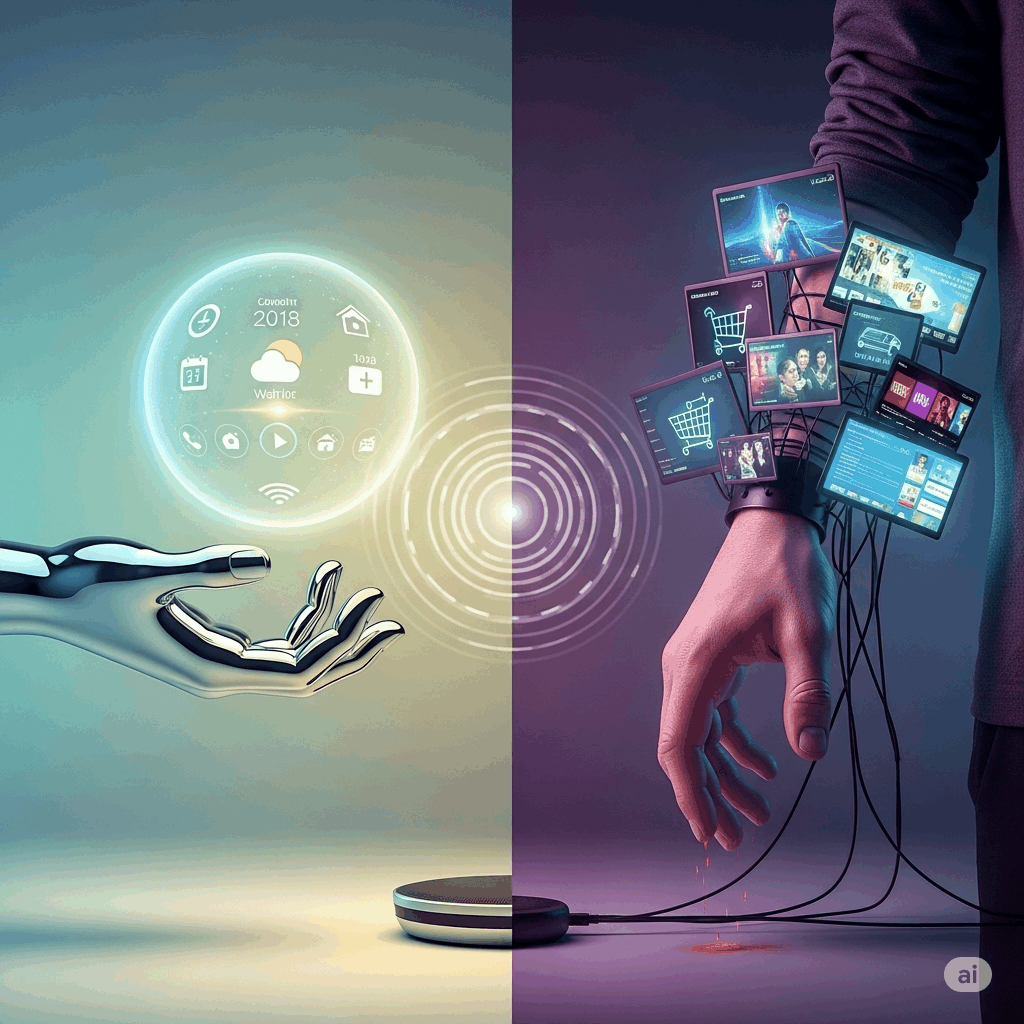

These phrases have become the background music of modern life. They are whispers of convenience, small incantations that summon information, organize our chaos, and guide our paths. The digital assistant—once a relic of science fiction—is now an omnipresent entity residing in our phones, our speakers, our cars, and even our watches. They are undeniably powerful, streamlining our lives in ways we could scarcely have imagined two decades ago. But as we delegate more of our cognitive load to these silicon servants, a critical question emerges, one that probes the very nature of our relationship with technology: Are we cultivating digital assistants, or are we nurturing our own digital dependence?

This is not a simple question of utility. It's a deep inquiry into the trade-offs between convenience and capability, between offloading tasks and losing skills. This article delves into this complex duality, exploring the symphony of convenience conducted by our AI companions and the silent, creeping risk of becoming intellectually and practically reliant on them.

Chapter 1: The Golden Age of Assistance

To understand the potential for dependence, we must first appreciate the profound appeal of assistance. Digital assistants like Amazon's Alexa, Google Assistant, and Apple's Siri have become masters of frictionless interaction. Their primary function is to remove barriers, reduce mental clutter, and save our most precious resource: time.

The benefits are tangible and multifaceted:

- Productivity Amplification: They are expert schedulers, note-takers, and reminder-setters. By offloading the mental juggling of appointments and to-do lists, they free up our cognitive bandwidth for more complex, creative, and strategic thinking. We don't have to remember to call the plumber at 2 PM; the assistant remembers for us, allowing our minds to stay focused on the project at hand.

- Information Immediacy: The sum of human knowledge is, quite literally, a question away. Settling a dinner table debate, converting measurements for a recipe, or getting a quick biography of a historical figure happens in seconds. This democratizes information, making curiosity an instantly rewarded trait.

- Accessibility and Empowerment: For many, digital assistants are not just a convenience; they are a lifeline. Individuals with mobility issues can control their home environment—lights, thermostats, entertainment systems—with their voice. People with visual impairments can have messages read aloud or get descriptions of the world around them. In this context, the assistant is a powerful tool for independence and inclusion.

- Seamless Home Automation: The "smart home" is orchestrated by these digital conductors. They connect disparate devices into a cohesive ecosystem, allowing for routines like "Good Morning" which might simultaneously raise the blinds, start the coffee maker, and play the news.

In essence, the "assistant" paradigm works because it augments our abilities. It handles the mundane so we can focus on the meaningful. It's the perfect secretary, librarian, and home manager, all rolled into one and available 24/7. So, where is the problem?

Chapter 2: The Slippery Slope to Dependence: Cognitive Atrophy

The danger lies not in the use of the tool, but in its overuse. It lies in the gradual, almost imperceptible shift from delegation to abdication. Every muscle in the human body, including the brain, operates on a "use it or lose it" principle. Neuroscientists call this synaptic pruning. When we consistently bypass a cognitive function, the neural pathways responsible for that function can weaken. This is the crux of the "digital dependent" argument: the risk of cognitive atrophy.

"What we are offloading is not just a task, but the mental exercise that comes with it. We are trading the small, satisfying friction of thought for the smooth, frictionless surface of an immediate answer."

Consider these key areas where dependence is quietly taking root:

The Erosion of Navigational Skills

Perhaps the most cited example is our relationship with GPS and mapping applications. Before smartphones, navigating to a new place required planning, map-reading, landmark recognition, and a sense of spatial awareness. It was an active cognitive process. Today, we blindly follow a blue dot on a screen, listening to turn-by-turn directions. While incredibly efficient, this outsourcing of navigation means many people no longer build a mental map of their own cities. If the battery dies or the signal is lost, they are not just inconvenienced; they are genuinely lost. The skill of orientation, once fundamental to human survival, is being voluntarily retired.

The Outsourcing of Memory

How many phone numbers do you know by heart? For many under the age of 40, the answer is likely one or two, if any. Our phones remember for us. The same goes for birthdays, appointments, and shopping lists. While helpful, this reliance can weaken our prospective memory (remembering to perform a planned action) and our general recall. The act of memorization, of creating mnemonic devices and strengthening associative links in our brain, is a form of mental calisthenics we are increasingly skipping.

The Stifling of Problem-Solving

When faced with a question, from the trivial ("How do I fix a leaky faucet?") to the complex ("What are the ethical implications of gene editing?"), the default action is no longer to reason, hypothesize, or consult multiple sources. It is to "Google it." We receive a packaged answer, often from a featured snippet, without engaging in the process of critical thinking, source evaluation, or synthesis of information. We become consumers of conclusions rather than practitioners of reasoning. The process of arriving at an answer, which is often more valuable than the answer itself, is short-circuited.

Chapter 3: The Psychology of a Surrender

Why are we so willing to hand over these cognitive reins? The answer lies in fundamental principles of human psychology. Our brains are inherently wired to conserve energy.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, in his book "Thinking, Fast and Slow," describes two systems of thought. System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive (e.g., knowing 2+2=4). System 2 is slow, deliberate, and requires effort (e.g., solving for $x$ in a complex equation like $3x^2 - 12x + 9 = 0$).

Digital assistants are the ultimate System 1 engine. They provide instant, effortless answers, allowing us to avoid the cognitive strain of engaging System 2. Every time we ask Alexa instead of thinking for ourselves, we are choosing the path of least resistance, a path our brain is naturally inclined to take. This creates a powerful feedback loop: the more we use the assistant, the easier it becomes, and the more effortful "real" thinking feels in comparison.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of anthropomorphism—attributing human characteristics to non-human entities—plays a role. We say "please" and "thank you" to Alexa. We give them human-sounding names and voices. This social lubrication makes it easier to build a relationship of trust and delegate responsibility, blurring the line between a tool and a teammate.

Chapter 4: Societal and Ethical Dimensions

The shift from assistant to dependent isn't just an individual concern; it has broad societal implications.

- Privacy as a Currency: These devices are built on data. To be truly "assistant," they must listen, learn, and record. Our conversations, location data, and daily habits become the raw material for improving the service and, more pointedly, for targeted advertising. We are paying for convenience with our privacy.

- Algorithmic Bias: An assistant is only as unbiased as the data it's trained on. If the data reflects societal biases (racial, gender, cultural), the assistant will perpetuate and even amplify them in its responses and actions. This can create a world where technology reinforces inequality under a veneer of objectivity. The probability model it uses, often a complex neural network, might learn a biased function $f(\text{input}) = \text{output}$ without any explicit programming to do so.

- The Homogenization of Experience: When everyone gets their recommendations for music, restaurants, and news from a few dominant algorithms, it can lead to a less diverse, less serendipitous culture. We risk being trapped in a "filter bubble," where our own preferences are endlessly reflected back at us, stifling discovery and exposure to different perspectives.

Chapter 5: Striking the Balance: The Path to Mindful Technology

The future is not about abandoning these powerful tools. A Luddite rejection of digital assistants is neither practical nor desirable. The goal is to reclaim our agency and establish a healthier, more intentional relationship with technology. It's about ensuring they remain our assistants, not our cognitive replacements.

The solution is mindful usage. Here are some practical strategies:

- Pause and Ask Why: Before you ask Siri or Google, take a moment. Is this a task that saves you from drudgery (like setting a timer), or is it a question you could answer yourself with a bit of thought? Choose to exercise your brain when the stakes are low.

- Embrace "Analog" Friction: Try navigating to a new place with your GPS turned off occasionally. Memorize a new friend's phone number. Read a physical book or a long-form article to build your attention span. These small acts of "inefficiency" are investments in your cognitive health.

- Use for Augmentation, Not Replacement: Use your assistant as a brainstorming partner, not a ghostwriter. Ask it for facts and data to support your argument, but craft the argument yourself. Use it to manage the logistics of a project so you can focus on the creative strategy.

- Conduct a Digital Audit: Understand the privacy settings on your devices. Be aware of what data is being collected and why. Make conscious choices about the trade-offs you are willing to accept.

Conclusion: The Choice Remains Ours

The digital assistant is a mirror. It reflects our desires for efficiency, knowledge, and ease. But as with any mirror, it's crucial to remember who is in control. The technology itself is neutral; its role in our lives is defined by our choices.

We can choose to be passive recipients of information, slowly trading our cognitive skills for effortless answers. In this future, we become the dependents, tethered to the cloud, our own minds softened by the lack of exercise. Or, we can choose to be active, discerning masters of our tools. We can use these assistants to handle the noise, freeing us to compose the music. We can leverage their vast knowledge to deepen our own understanding, to ask better questions, and to solve more significant problems.

The line between an assistant and a dependent is not drawn by a programmer in Silicon Valley. It is drawn by each of us, every day, with every question we choose to ask and every thought we choose to think for ourselves. The choice, for now, remains fundamentally human.